Collaborating on the Design of Collaboration Activities

From November to December, the project began to confront the challenges of the proposed innovation with role-based collaboration in a game setting. A natural collaboration that happens organically between team members is one thing. However, creating a game-like setting where students take on professional identities and act within those identities to support group actions or group moves requires a deliberate design. Looking at the games we had studied (see November Newsletter), each one had used roles that had given those players special abilities (superpowers) that allowed them to make moves on their own. However, the nature of the activities in these games was unlike a cybersecurity crisis response that this project is planning to teach about. In addition to having a fun and engaging game, we want our student players to take away some knowledge of the complementary nature of STEM professional work. Our design is then in some ways more specific than the games we studied. Deciding which roles to use and how to structure collaboration tasks or tasks where collaboration is possible is part of this project’s coming work.

Big Questions from Analyzing the November Design Meeting

Following the November 22 meeting where many brainstorming artifacts were developed, a team at Maryland began to analyze the work that was done; pulling out ideas and themes. These analyses led us to begin looking at the issue of roles and how some roles might have different kinds of information to access. An idea that had been suggested early in the project proposal has received a lot of consideration that we would provide some information resources (ex: a dataset) to each of the roles that they would have that other roles would not. This structure would create opportunities to collaborate. This led to questions about the kinds of datasets players could have access to. Some other big questions that emerged from this time include:

- Will players have conflicting priorities / competing interests? Expert interviews had shown that the priorities of forensics specialists for example and public safety are different, and they might approach the same situation wanting to do different things.

- Will there be multiple scenarios? Is there one “master” scenario that everyone gets? [may drive the competition/co-op views]. Will each role be shown different information about events that are unfolding?

- What will the move mechanics be? How many actions will any player be able to do at any given point in the story? Will there be costs and payoffs of decisions? Will the turns be sequential or simultaneous?

- How do we represent a cyberattack visually? Will there be a map? At what detail? Would students need to understand the underlying network infrastructure or attack surface?

- How realistic should the scenario(s) be? Do we want to use the NIST Risk Pyramid to structure our attacks? How do students succeed in their assessment covering the attack surface?

- How will students work with information resources? Do we curate and help students filter them?

- Will there be an economic model in the game? Will we ask students to consider the financial impacts of various options such as ransomware attacks? Will players have points different from the points for their teams?

The working session was fruitful in helping us understand some of the decisions we could be making about the design to come.

Looking at Roles

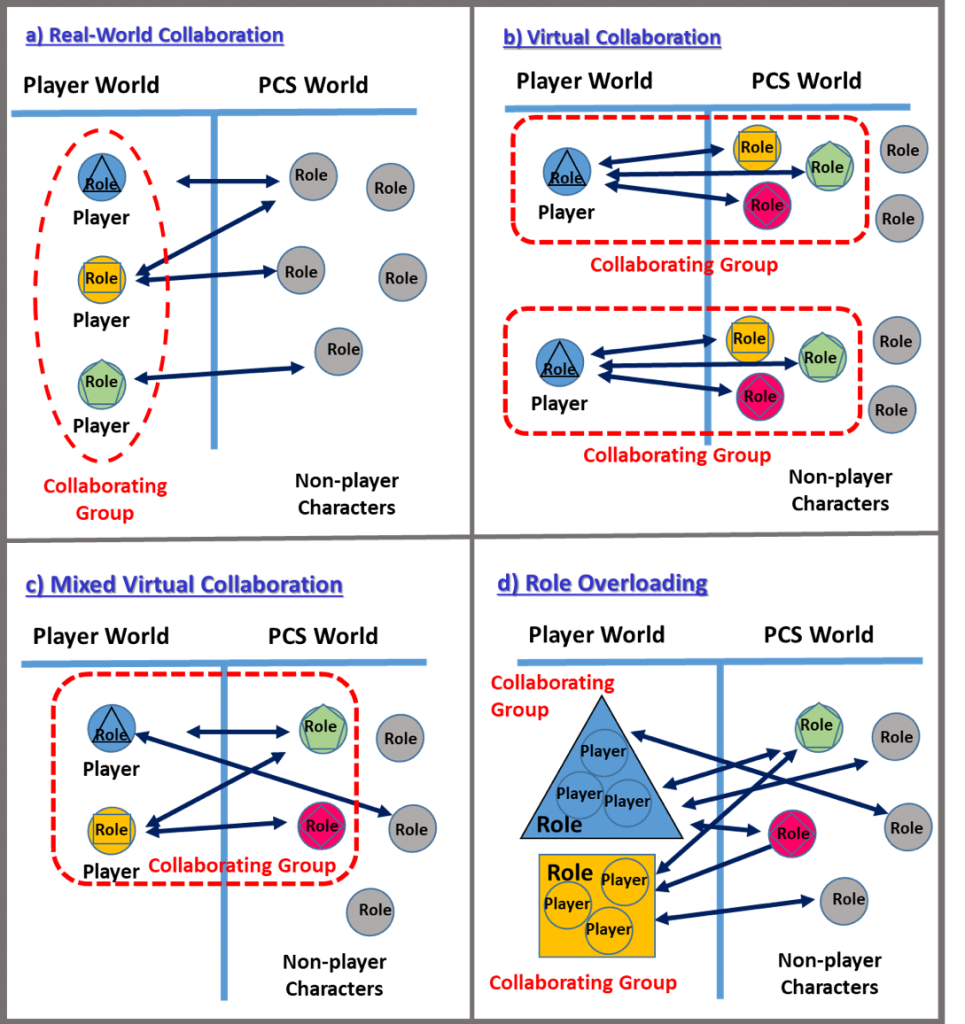

Foundational to the design of the collaborative STEM PCS experience this grant is developing is the conception of roles and how they will interact with each other and with the narrative characters. The PCS provides a set of characters that represent co-workers and others through the transmedia interface to the player to provide a simulated social experience. Our review of various games (See November Newsletter) showed different ways roles were designed into other game designs. When considering the architecture for this project, there appear to be a number of different ways the player and non-player characters can be arranged as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Different Approached to Structuring Collaboration

The different approaches represented in Figure 1 are alternatives to creating a structure for collaboration. They are not necessarily mutually exclusive. In option 1.a, the collaboration happens between players (students) in the real world and possibly record their messages inside the PCS platform. This option, titled Real-world Collaboration has a dependency on all players participating, which is not always assured with undergraduate students. Virtual Collaboration shown in Figure 1.b would avoid these challenges by having students work individually, and their ‘collaboration’ would occur entirely within the PCS as either automatic agents in the PCS or as human mediators (perhaps teaching assistants) sometimes known as game runners who play the part of collaborators but are not physically present. The third option represented in Figure 1.c is a mixture of the two where there are a small number of real-world characters in the collaboration group and then some other number inside the PCS. In addition to mitigating the participation risks, this approach would tend to drive more communication through the PCS where it is automatically captured and available for analysis without additional transcription efforts.

The final choice represented involves having more than one actual player participating in a role. This approach has been taken by the International Communication & Negotiation Simulations (ICONS) project at the University of Maryland (icons.umd.edu) that has been developing simulations to support learning in a range of settings that include military, education, crisis management, and wargaming for over 30 years. Since many of the ICONS players are working professionals, there are similar participation challenges resulting from work demands during the time of the simulation, and this option mitigates that risk by allowing more than one player to inhabit a role. A challenge to this approach may be that if the players are conversing while collaborating, but outside of the game in which case the communication is not as easily captured for analysis.

Representing the Design

Working across three institutions with different academic calendars and in different time zones brings challenges into the design process. Compounding this challenge is the fact that our research team is composed of many individuals that are often only supported on the grant for a small amount of time. Our design process can then be seen as collaborative over distance. Communicating about our design process is then important, and the project is experimenting with digital whiteboards that would allow collaborators across the different institutions to produce and comment on different design options.

Studying the Design Process

We are also supporting a complementary research agenda by Jason McDonald of BYU, who studies creativity and design processes. As we develop design documents, we are curating a versioned history of them so that he and his team can review the progress and also advise on best practices going forward. BYU has developed an additional institutional review board (IRB) process, and researchers across the institutions are giving permission for recordings of their collaborative discussions and design artifacts to be analyzed outside of this grant.

Careers In Play Leadership Team

Phil Piety, PhD. University of Maryland iSchool (PI and Learning Analytics). ppiety@umd.edu

Beth Bonsignore PhD. University of Maryland iSchool (Co-PI and Design-based Research), ebonsign@umd.edu

Derek Hansen, PhD.Brigham Young University (Co-PI and Game Technology). dlhansen@byu.edu

Dan Hickey, PhD. Indiana University School of Education (Co-PI, Learning Theory and Assessments). dthickey@umd.edu