Moving into the Design Process

November was a transitional month as the early analysis and project organization efforts began to yield to the design process. Going into this project, the team recognized that the technology and instructional approach would be both similar to past Playable Case Study (PCS) projects and different from past PCS efforts in important ways. Creating a collaborative, role-based PCS where the players would all work together to solve a common challenge would be new. Our initial research had shown that while many have discussed collaborative game designs in the literature, there were few examples that could be used as a template. Concepts like “jigsaw pedagogy” make a lot of sense, but designing this into classroom activities is challenging. This project is then going to be developing a design that is original in some important ways. A fall project meeting was held on November 21 and 22 when two members from BYU and two from Indiana visited Maryland was a chance for us to engage with the design issues and also begin to develop our processes for conducting design sessions and collecting/managing data from these sessions for analysis that will become increasingly important in the spring of 2020 and later.

Looking for the Complete Four-Dimension Design

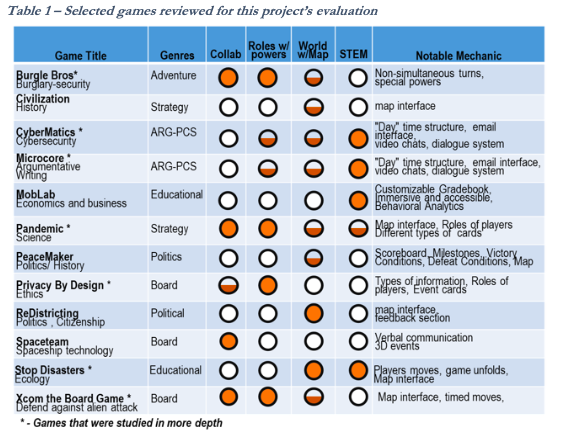

Through the early part of the fall, the Games Research Team at Maryland had been looking at different kinds of games, both tabletop and digital, that could show different approaches that could be used in the new PCS design for this grant. The team identified four characteristics that are central to this project’s mission:

1. A collaborative model where players work together to solve a problem

2. Player roles with specific strengths (superpowers) for each role

3. A World at the scale of a community with a map and locational issues

4. A STEM context where the roles involved science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM)

These criteria were used for a search of games. The research team expected to find many that fit these criteria, but in fact, none were found that had all four dimensions. Of those twelve, six had two or more areas strongly represented and those six were analyzed further to understand the game mechanics and design features as shown in Table 1.

Those six games included two prior PCS versions, Pandemic (referenced in the proposal), Privacy by Design (developed in the iSchool), Stop Disasters developed by the UN, XCom the board game, and Burgle Brothers that involves a team attempting to break into a museum and avoid guards, which was in some ways an inverse design to this one where the players will attempt to prevent an attack.

Expert Interview Team: Discovering Building Blocks of the Narrative

Over the past couple of months, the Expert Interview Team had a number of interviews and co-design sessions with practitioners in cybersecurity positions and those with advanced knowledge of the cybersecurity field. What emerged from these interviews are elements that could become parts of the narrative that this project will need. The interviews and sessions provided a number of roles and kinds of actions that could be used in this project. Some of the roles explored include Network Engineers, Systems Administrators, supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) engineer and IS managers who might be parts of teams have roles in preventing or responding to a cybersecurity attack. The interviews also showed a number of information resources that could be used by cybersecurity professionals, including: Lockheed Martin’s Cyber Kill Chain, the Cyber-disruption index, Network Logs, Email logs, etc.

This research did not give a complete picture of this project’s architecture. What they provided were meta-design elements that could be used in the design of the new collaborative PCS model. For example, in showing some of the kinds of information resources different professionals might use in combating cybersecurity threats, the expert interviews were showing how a relationship between information resources and professionals working in roles is authentic and validates one of our early design ideas about role-based collaboration involving, in part, one person having access to information specific to their role and then translating that information for others on their team. Similarly, the kinds of roles that emerged in the interviews were indicative of some of the kinds of professional identities this project’s PCS might develop, but the nature of a game will involve some standardization of these roles and other design considerations.

Graduate Student All-Day Workshop November 21

Dan Hickey from Indiana and his PhD student Grant Chartrand conducted an all-day workshop worked with the project’s graduate students from Maryland and BYU how to read scholarly pieces within an academic tradition and how the citation process is purposeful and how when writing their own pieces it is important for them to demonstrate knowledge of the field for their reviewers.

Naturally, the examples and context for this workshop came from Expansive Framing, the approach to designing learning activities that forms the core of one of the project’s research questions. One of the goals of this workshop was to help our graduate students understand to understand Expansive Framing so they can help with the design of the student activities using those concepts.

November 22 Design Session: Brainstorming Tasks

On Friday, November 22, project members from Maryland, BYU, and Indiana gathered for an all-day design session. The goal of this meeting was to bring together the initial findings from the games research and expert interview teams so that all in the room would have some understanding of the kind of work that had been going on in other parts of the project. The team members from different institutions were then grouped into four working groups so that each would be connecting with others from different institutions. These working groups had two purposes. First, to take some of the emergent narrative building blocks that were developed through expert interviews and put them through a design process to question, extend, and problematize them—to see how they might be operationalized in terms of real student work. What was brought out of the expert interviews acted like the ‘starter culture’ for a broader design process.

The working sessions involved three activities. The first two activities had four groups of four members each (one participating remotely from BYU) work on a simple design task. The first task asked each team to describe the specific information resources that one role might have access to while others would not. The second task asked the teams to describe different kinds of information that could be shared between roles. Both of these tasks relate to a prominent design concept that has been discussed that our collaboration would involve information exchange. In both cases, the teams were given just three of the many roles that were identified through expert interviews.

Both of these brainstorming activities invited the working groups to provide any information or clarifications that made answering these specific questions challenging. They invited the members to use the format provided or go beyond in any way that would help to explain their thinking. These tasks then acted as prompts for brainstorming activity to help draw out of the teams’ knowledge related to these questions of information that the interviews had not and to help us think in terms of structuring the collaboration activities. The reason for this is that in our design we will need to be specific about the kinds of information each role has access to and the kinds of cross-role collaborations we see possible. These exercises helped the team begin to think in those specific terms. By asking for clarifications the process became expansive allowing the team members to bring their considerable knowledge to bear on the area.

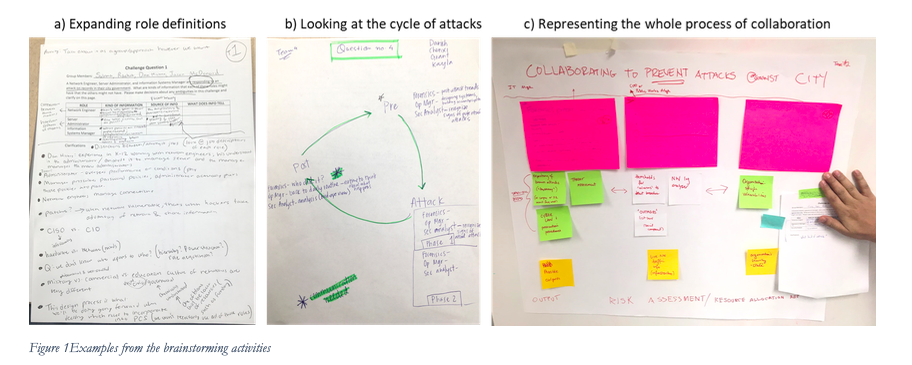

These brainstorming tasks were designed to be open and teams were encouraged to go beyond what was asked for. Figure 1 shows some of the different ways the teams worked expansively. In 1a, the team discussed the fact that the roles that they had been given would normally be in some kind of organizational hierarchy, which was not mentioned before, but likely will become a design feature. The work represented in 1b shows how cyberattacks are not just a singular event, but occur in a cycle. In 1c, the group was looking at the process of collaboration comprehensively and using the original prompt as a reference (see right side of figure), but used other representational tools such as sticky notes and posters.

The third activity created four new working groups with one member from each of the previous working groups. This activity asked the members to share what we had learned about one of four different areas:

1. Roles: who are the participants in a cybersecurity event

2. Event structure

3. Information resources: specialized datasets and other information each role or a team might have

4. Scenarios to consider from ransomware attacks to infrastructure attacks

Working at whiteboards the teams then presented their synthesized findings. Images of all artifacts developed by all groups were captured digitally and saved in project archives.

Beginning the Analysis of Design Records

Looking into the project’s next few years, there are many events where we will collect rich records that will be collected, curated, and analyzed. The November 22 design session was the first one and gave the project an opportunity to work through the logistics of collecting the records that can be in the paper, whiteboard, and multimodal form as the example of Figure 1c shows.

The proposal indicated we would use large format scanners to digitize the artifacts and then not maintain paper records. We ended up decided we could do more with the use of basic mobile phone technology by capturing an image with a handheld device and then uploading those images to a curated internal site for subsequent analysis. The records were then transcribed and important findings and questions synthesized from the raw records.

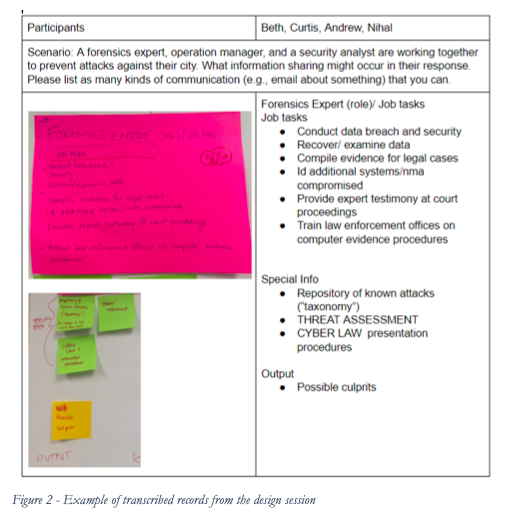

Figure 2 shows an example of the kind of post-event work that was done with the data. Each of the images collected from that day was put into a single document where it could be transcribed. Important questions and highlights from the records are then drawn out into another summary document. This process of transcription and interpretation was used with the Maryland team as a way to show them the kind of records we would be collecting and the interpretation process we would be using as we get deeper into data collection. In addition to getting some additional ideas and understanding our design challenge more, it helped as a training activity for our new undergraduate and graduate researchers.

Later, we will use this same approach when we collect records that may have personal identifying information (PII) related to students. In that case, we will upload the images to a secure server that is available only to the research team.

Careers In Play Leadership Team

Phil Piety, PhD. University of Maryland iSchool (PI and Learning Analytics). ppiety@umd.edu

Beth Bonsignore PhD. University of Maryland iSchool (Co-PI and Design-based Research), ebonsign@umd.edu

Derek Hansen, PhD.Brigham Young University (Co-PI and Game Technology). dlhansen@byu.edu

Dan Hickey, PhD. Indiana University School of Education (Co-PI, Learning Theory and Assessments). dthickey@umd.edu